Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

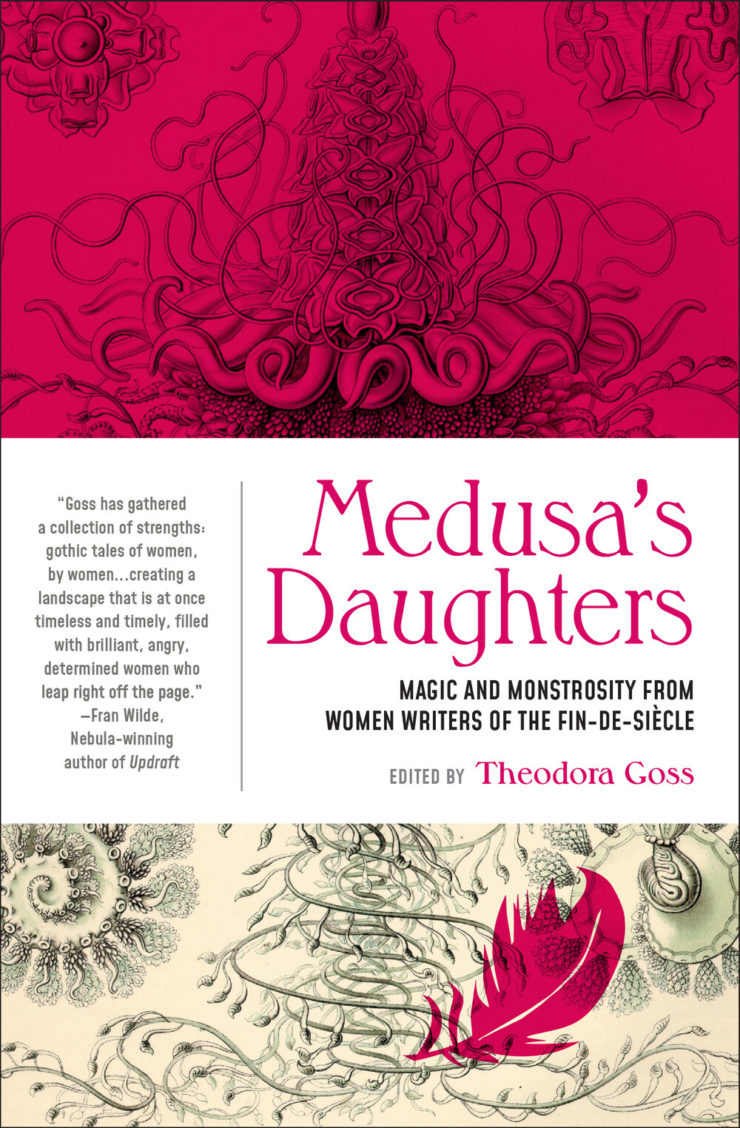

This week, we cover Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “When I was a Witch,” first published in the May 1910 issue of The Forerunner. You can find it most recently anthologized in Theodora Goss’ Medusa’s Daughters anthology. Spoilers ahead!

“I might as well make a good job of it while this lasts,” said I to myself. “It’s quite a responsibility, but lots of fun.” And I wished that every person responsible for the condition of the subways might be mysteriously compelled to ride up and down in them continuously during rush hours.

Unnamed female narrator was once a witch. Hers was an inadvertent Satanic contract with rules unstated, left for her to infer from subsequent events. Having accidentally unwitched herself, she’s recreated the “preliminaries” to her enchantment as exactly as possible, but without success.

Her too-brief witchhood starts on a sultry October 30th, at midnight on the roof of her apartment building. It’s been a too-typical urban day: Sleep-robbing noise from dogs and cats the night before, ersatz cream and a too-old egg for breakfast, morning papers too mendacious or salacious, a taxi ignoring her and a subway guard closing the car door in her face, and once finally onboard all the pawing from fellow riders and herding from officials and men lawlessly smoking and women attacking her with their “saw-edged cart-wheel hats.” The roof offers solitude, at least. Or not quite solitude—a black cat, starved and scalded, appears from behind a chimney and mews dolefully.

Narrator watches a cab pass on the street below. Its driver whips his exhausted horse. She wishes aloud, with all her heart, that anyone who wantonly hurts a horse will feel the pain while the animal goes unscathed. The driver whips the horse again, and screams himself. Narrator doesn’t make the connection immediately, but the black cat rubs against her skirt and mews again. Narrator regrets how many homeless cats suffer in cities. Later that night, though, kept awake by yowling felines, she wishes all the cats in the city “comfortably dead.”

Next morning her sister serves her another stale egg. Narrator curses all the rich purveyors of bad foods to tasting their own wares, to feeling their overpricing as the poor do, and to feeling how the poor hate them. On her way to work she notices people abusing their horses, only to suffer themselves. When a motorman gleefully passes her by, she wishes he’d feel the blow he deserves, have to back up the car and let her aboard with an apology. And the same to any other motorman whoever plays that trick!

Her motorman, at least, backs up and apologizes, rubbing his cheek. Narrator sits opposite a well-to-do woman, gaudily dressed, with a miserable lapdog on her knees. Poor inbred creature! Narrator wishes all such dogs would die at once.

The dog drops its head, dead. Later the evening papers describe a sudden pestilence among cats and dogs. Narrator returns her attention to horses, wishing that anyone who misuses them will feel the consequences of the misuse in their own flesh. Soon a “new wave of humane feeling” raises the status of horses—and people start replacing them with motor-driven vehicles, a good thing to narrator’s way of thinking.

Buy the Book

A Half-Built Garden

She knows she must use her power carefully and in secret. Her core principles: Attack no one who can’t help what they do, and make the punishment fit the crime. She makes a list of her “cherished grudges.” All manner of corrupt businesspeople and authorities feel her righteous wrath. Reforms proliferate. When religions try to take the credit, she curses their functionaries with an irresistible urge to tell their congregations what they really think about them. Pet parrots she curses to do the same to their owners, and their owners to keep and coddle the parrots nevertheless. Newspapers must magically print all lies in scarlet, all ignorant mistakes in pink, all ads in brown, all sensational material in yellow, all good instruction and entertainment in blue, and all true news and honest editorials in black. Journalistic riots of color slowly tone down to blue and black. People realize they’ve been living in a “delirium” of irrationality. Knowing the facts improves every aspect of society.

Narrator has enjoyed watching the results of her “curses,” but the condition of women remains a sore point. Must they be either expensive toys or thankless drudges? Can they not realize the true power of Womanhood, to be loving and caring mothers to everyone, to choose and rear only the best men, to embrace the joy of meaningful work? With all her strength, narrator wishes for this universal feminine enlightenment!

And—nothing happens. That wish isn’t a curse. It’s white magic, and her witchery can do only the black kind. Worse, trying for white magic has stripped her of power and undone all the improvements she’s already wrought!

Oh, if only she’d wished permanence on her “lovely punishments!” If only fully appreciated all her privileges when she was a Witch!

What’s Cyclopean: Narrator feels that women’s behavior in a constrained society is “like seeing archangels playing jackstraws.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Women aren’t supposed to swear. Disturbing things happen when they do.

Narrator, though, definitely falls prey to the “not like other girls” fallacy, describing rich women as fake and childish (never mind the incentives for those hats) and others as “the real ones.”

Weirdbuilding: “When I Was a Witch” follows in the footsteps—though not always the patterns—of many stories about the hazards of getting what you wish for.

Libronomicon: Newspapers are first made more entertaining, then improved, by color-coded fact-checking.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Narrator says, of inaccurate reporting: “It began to appear as if we had lived in a sort of delirium—not really knowing the facts about anything. As soon as we really knew the facts, we began to behave very differently, of course.” If only it were that simple!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Sometimes you read a piece by a famed author, and understand why they’re rightly hailed as a genius. And sometimes you read a piece by a famed author, and feel the warm fondness of knowing that sometimes even geniuses just kinda want to blow off steam at everything pissing them off. (I’m thinking here of Le Guin’s Changing Planes, which obviously got her through many unpleasant airport delays. You go, Ursula!)

I do see, however, why it’s “Yellow Wallpaper” that gets perennially anthologized. It’s incredibly creepy, makes extremely pointed points about gender, and has 100% less gratuitous murder of all the cats and dogs in New York City.

I’m not going to say much about all those dead dogs and cats, other than that anyone who could come up with better solutions for horses and parrots ought to have been able to do better, even with black magic. Also, what the hell? Maybe Gilman was allergic or something? Or maybe it’s meant to point toward the magic’s wickedness early on. One doesn’t often get readerly sympathy by killing dogs.

Actually, Le Guin is an interesting comparison, because the extremely basic outline of “When I Was a Witch” has kinship with later work-of-genius The Lathe of Heaven. Or indeed with many stories about wish-related peril, from the Arabian Nights to Labyrinth. The usual pattern is inverted, though: only selfish, harmful wishes work. And they work exactly as intended—no backlash against the wisher, no twisting the meaning of words. Our former witch suffers no consequences, save that when she finally makes a truly kind wish the game comes to an end.

That final, unfulfilled wish, is where this becomes recognizably Gilman: it’s a wish for universal female empowerment, for the betterment of both women and the world as a whole. And it casts the whole rest of the story in a different light. From the start, Narrator traces her bitterness to the degree to which she’s not supposed to be bitter. Women are angels of the house, after all. They don’t swear, let alone wish cute animals dead. What festers, under that mandatory veneer? Is a witch just someone who refuses to conform to angelic norms?

Jackson’s witch suggests it’s something more: not just breaking social norms, but breaking them in order to do harm. But then, if people are going to accuse you of harm if you veer from the standard at all—and if you’re having a miserable day—the temptation to actually do the harm might be high.

Narrator assumes that there’s a Satanic pact involved, but it’s never actually confirmed. There’s a black cat, sure. And the wish that breaks the spell is the first that does no obvious harm. No, not just that. It’s the first that isn’t a wish for harm. There are certainly people who would feel aggrieved (and deserve it) if all women suddenly came into their power and refused to be taken advantage of. But the wish doesn’t focus on their disgruntlement—whereas the wish for automatic universal fact-checking in newspapers, while it does considerable good, is framed as an embarrassment to journalists. It doesn’t seem very Satanic to allow a wish for ill to do good, does it? It’s traditionally the reverse.

Something weirder is going on here. And I haven’t the first theory what it is. I wonder if Gilman did?

Anne’s Commentary

I have big sympathy for Gilman’s devil—her witch, that is, not Satan in black-cat guise. Not that I have anything against demonic felines, even when they’re still freshly scalded by the lava-geysers of Hell, which is not their best look. I’m tempted to call the unnamed narrator Charlotte, given how closely her mindset resembles her creator’s. Let’s say Charlie, to differentiate the two.

Charlie’s modern industrial/commercial world is too much with her, much as it was with Wordsworth about a hundred years earlier:

“The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers; –

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!”

For Charlie, the noise and dirt, the casual cruelty and empty display of the city, are sufficient microcosm of the mess humanity’s made of the world. Passive acceptance may be enough for her sister; though as helpless to change the way things are run around her, Charlie burns to make improvements, right wrongs, punish malefactors, damn it! I think that last, the punishment bit, is crucial to the path her magic takes. We’re back to Yoda’s second and third steps to the dark side: anger that leads to hate, hate that leads to suffering. Up on the roof, Charlie’s seething with so much frustration that her Sith lord senses a potential apprentice and sets up a test. How Charlie responds to the cabdriver whipping his horse will determine her eligibility for the witchcraft Satan can provide. Presumably she could have wished, with all her heart, that empathy might stay the driver’s hand. Instead she heartily wishes that the pain he inflicts should ricochet onto himself. It may be that Satan provides the magical agency for this first ricochet, and then through his cat-avatar brushes the agency—the witchcraft—off onto Charlie.

I’m not judging, Charlie, lest I judge myself. I have an ongoing wish that I could change the world via witchcraft—and, I’m afraid, I also share with Charlie an impulse to reform through punishment. Does reason or cynicism power a conviction that the only way to make evildoers desist is to eye-for-an-eye them—with the added bonuses that the targeted victim gets to keep their eye? Listen, you can’t be nice to those people; all they understand is a good hard smack across the kisser, actual or metaphorical, yeah.

Did you hear my James Cagney impression there?

The question is whether power must corrupt in direct proportion to the intensity and scope of that power. Charlie wants to be a good and just witch, but right from the start her personal comfort and prejudices lead her astray. Caressed by the black cat, she feels a rush of compassion for all the poor suffering felines in the great city. A couple hours later, the suffering yowl of one such feline irritates her into the wish that all the city’s cats fall “comfortably” dead.

Which they do, to be followed the next day by all those pitiful lapdogs overdressed and overfed women haul around. That edict simultaneously “saves” the dogs and punishes their owners, double score! But double score for whom?

As Charlie discovers, she can’t use her magic to perform tricks like knocking over wastebaskets or refilling ink bottles. Those outcomes would be neutral, trivial, not backed by the passionate desire that enables both her social reforming efforts and the indulgence of her “grudges.” Charlie has set up good rules: Hurt no one who can’t help what they’re doing, and make the punishment fit the crime. It’s questionable, especially in respect to her grudges, whether she consistently follows these rules—or even can follow them. Black magic wouldn’t permit such ethical purity, would it?

Charlie does achieve some big social improvements, or so she tells us. She’s most specific about reforming the newspapers through chromatic shaming. Once the papers are printed all in blue (good fun, instruction and entertainment) and black (true news and honest editorials), she believes that a steady diet of facts has people on the road to rational behavior and will create the foundation for her utopia. Things are going well. So well Charlie forgets to be angry.

Wait for the supreme irony. Once Charlie has the emotional space to step back from punitive measures, she can begin to envision the ultimate emancipation of women from inane distractions and drudgery, an emancipation that will allow them to embrace “their real power, their real dignity, their real responsibilities in the world.” Instead of anger, it’s the energy of hope and joy and wonder that she pours into her magical wish for this consummation of all her reforms.

Sorry, Charlie. Your anger got you signed up for black magic. White magic is so incompatible with your abilities that not only does it fail you, it blows up your witchery and all it’s ever created. All those “lovely punishments,” gone!

“Lovely punishments,” two critical words for understanding Charlotte’s take on Charlie’s story? To employ the coercion of pain—in fact to enjoy it, however her world has shaped her for this approach to power—leaves Charlie a flawed agent for the exercise of white magic. She can’t take the big step up from forcing people to behave well to inspiring people to do so.

That’s assuming it’s even possible for an angel to succeed with flawed humanity. A devil can at least get a semblance of the job done, but is a semblance of reform, virtue forced, a viable start toward the freely embraced virtue which is the genuine basis for utopia?

I don’t know. If I get to be a witch, maybe I’ll leave people alone and stick to ridding the world of mosquitoes and all those other biting and stinging and bloodsucking invertebrates that seem to single me out for their attentions. I’ll replace them with nonirritating species, I swear, so whatever eats them won’t starve.

If I decide to get rid of chihuahuas, though, no replacements. We black magicians have to indulge our prejudices somewhere.

Next week, we continue N. K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with Chapter 6: The Interdimensional Art Critic Dr. White. That doesn’t sound at all worrisome.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic, multi-species household outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.